Crass tell musicians: “It is our responsibility to warn of what is happening in this dangerous world rather than just covering up the agony with mindless entertainment.”

From the NME, 29 January, 1982.

Tag Archives: Crass

Crass Squat Gig

Here’s the Crass set from the squatted Zig Zag Club in 1982. They even start with a poem.

Rock Against Crass

Special Duties’ singer Steve Arrogant in the letters pages of Sounds, 18 November, 1982.

The Essex poonks had a campaign against Crass, and a single ‘Bullshit Crass’. In the 2004 Ian Glasper book Burning Britain: The History of Punk 1980-1984 from Cherry Red Books, Arrogant explains his dislike of Crass: “It was the fact that they said ‘Punk was dead’, and they played this really tuneless music. I saw them as almost a religious cult”.

No Bottle

Due to lack of bottle by the promoters of the venues we’ve approached, the ‘Rock Against Crass’ gig will now be unable to go ahead.

We would like to take this opportunity, however, to thank all the bands who got in touch with us concerning the cause. In case the bands in question do not wish to be mentioned unnecessarily as being Anti-Crass a full list of them is being withheld, but thanks anyway. The talking stops here but the feeling remains. Sorry to the bands who we promised a gig, but the venues just don’t want to know.

Steve Arrogant, Essex

Bloody Revolutions

Ian Bone, a year before forming Class War, throws a punch in the Crass v Oi handbags raging on the Sounds letter pages in 1982. This from Sounds, 26 June, 1982. The same edition also featured a response from a skinhead girl.

Children of the revolution

What both Garry Bushell and Crass ignore in their argument about whether Oi bands are more revolutionary than Crass bands is the possibility that playing music isn’t revolutionary at all … that it’s merely a distraction to stop us fighting the class enemy more effectively.

A good example of this was the recent CND demonstration in Hyde Park. As your enthusiastic correspondent naively described it … ‘As a sheer spectacle in itself it must be second to none.’ Exactly, it was a spectacle, something for us to gawp at, and remain completely passive in our consumption of, whether it was punk poet Vi Subversa or lefty trade union leader Arthur Scargill.

When a large group of anarcho-punks, bored with the speakers, decided to go over to County Hall where the GLC were organising a free concert with one of their favourite bands, the Mob, they were quite rightly harangued by a couple of other anarchists … “Go on punk rockers, go and listen to your bands, exchange your boredom here for your boredom there, be passive consumers.”

Some were persuaded to stay and join the 300-400 anarchists who rejected the boredom and passivity of both events and trashed down Oxford Street before being rounded up by SPG snatch squads. Meanwhile the rest of our anarcho-punks gawped at Vi Subversa and Captain Sensible in Hyde Park or other cult heroes at County Hall.

If the GLC or the government organised free concerts by Crass or Bushell’s heroes all summer, there would never be any danger of last summer’s rioting happening again. Crass’ dead-end pacifism is only the most obvious political expression of the passive consumption of the Oi merchants.

The only possible justification for being in a band is to rebel against the vicious system we live under. When we, the Living Legends, played with Crass in Swansea last year they pulled out the plugs on their PA when we were playing because they said we were inciting violence against the system through our attacks on the Pope, Reagan, Queen Mother, etc.

They also refused to let John Jenkins, who had come out of prison after serving a 10 year sentence for a bombing campaign against state property (during which no-one was injured) introduce our ‘Burn Down Your Holiday Homes’ number because he was a ‘convicted terrorist’.

With anarchist bands like this, and Bushell’s even worse alternatives, who needs enemies?

Ian Bone, directly accountable to the rest of the Living Legends.

Categoiry

A skinhead girl chucks her two penn’orth in to the Sounds letter page, 26 June, 1982, during the Crass V Oi handbags.

Dear Bushell/Crass,

what all this petty bitching? I’m a female skinhead and I’ve got the three Oi albums and singles. I’ve also got Crass LPs and singles – yes, together in one record stand!

Why waste each other’s valuable time on stupid petty bitching? I know you disagree on a lot, but you also agree on one vital thing – punk! You’ve both done a hell of a lot for punk!

I call punk good, raw aggression, anti-politics, anti-racist, anti-war, just pure power!

This is what I thought you two also believed in.

I don’t categorise punk into Oi/skunk/skin etc., but I wouldn’t slag anyone if they did. But you must agree we’re all in the same ‘sinkin’ boat’, surely?

Stop arguing with yourselves and start some good, clean destruction against the state and system – peacefully!

How’s that then?

A female skin who wants to start a serious band.

Anarchy In The UK

This article about Britain’s Anarchist movement appeared in New Society, 22 November, 1979.

Anarchy In The UK by Ian Walker

At the end of Angel Alley in Whitechapel, the name of Kropotkin is written in whitewashed capitals. In a small room on the first floor of this building, eight men are collating the latest issue of Freedom, the anarchist paper founded by Kropotkin himself. An adjoining room is stacked with back numbers of Freedom, going back to 1866, in brown envelopes. There are pictures of heroes on the walls, and a poster: ‘All excercise of authority perverts. All subordination to authority humiliates.’

An A in a circle, spraypainted on walls in city streets, is the nearest most citizens come into contact with anarchism. The media spectacle that the anarchists themselves find comic and tragic, has no room in its schedules for the ideas and actions of the anarchists. But they have chosen to live on the margins, in a kind of political exile, and that is the way it must be. The support group set up on behalf of the five anarchists now facing conspiracy charges at the Old Bailey is called, appropriately, Persons Unknown. Marxists say that anarchists don’t live in the real world. But a lighthouse is as real as a supermarket.

Some of those who shop in the supermarket of ideas are attracted to anarchy, but most aren’t. It does not have the academic respectability of Marxism. (Students, after all, answer questions on alienation under examination conditions.) Yet the anarchists have always had an influence, even in Britain, out of all proportion to their numbers. William Morris, Shelley, Oscar Wilde, Edward Carpenter, Herbert Read, Augustus John, were all anarchists of sorts. Over the last 15 years, anarchist ideasand methods of organisation have had an impact particularly on the ‘alternative society’ of lifestyle politicos, on the women’s movement, on squatting and other forms of community activism, on punk.

I have been speaking to different kinds of anarchists. Orthodox ones like members of the Freedom and Black Flag editorial groups. Unorthodox ones like a punk band called Crass, and an electrician who produces a libertarian motorcycling magazine, On Yer Bike, in his spare time. I went along to a meeting organised by a libertarian group called Solidarity, and to the Persons Unknown trial.

The weight of ideology and history hangs as mustily in the atmosphere at the Old Bailey as it does, in a different way, at Freedom’s HQ.

‘I said, “Are you denying you’re an anarchist?” “No!” he said.’ A Policeman is giving evidence. He has a working class accent – unlike the barrister questioning him, who possesses the voice which seems to fit the oak and wigs and the motto on the crest which says DIEU ET MON DROIT.

Two of the defendants, Iris Mills and Ronan Bennett, were active in Black Flag, I am told by two members of Black Flag I meet in a pub. This is the ‘organ of the Anarchist Black Cross’. It is a paper set up by Stuart Christie after his release from a Spanish jail, where he was serving time for an alleged attempt on Franco’s life. Christie is now up in the Orkneys, running a publishing house called Cienfuegos Press.

Rob is 28, and Kate 31. They speak with pride of two anarchist veterans still active in Black Flag: Albert Meltzer and Miguel Garcia. Garcia fought in the Spanish civil war (always called the Spanish Revolution by anarchists) and was imprisoned for 20 years. ‘Black Flag has got people throughout the world, helping political prisoners where they can,’ says Kate, who has not lost her Australian accent. She is a friend of Iris Mills. ‘I met Iris in Australia. She stayed in the same house. That’s how I first got involved in anarchism.’

Ronan Bennett was in Long Kesh, awaiting trial, when he first came across Black Flag, which is sent out free to prisoners who request it. ‘He wrote to Black Flag,’ Kate says, ‘and Iris wrote back to him about anarchism. That is how they first made contact.’ Mills and Bennett were subsequently charged with ‘conspiring with persons known and unknown.’

Rob and Kate seem unaffected by recent movements in libertarian politics. Kate brushes aside feminist critiques of language: ‘I think it’s a load of shit myself. I call people “chairman”.’ They cling to the anarchist eternities.

Marxists and Trotskyists are every bit as much their enemy as capitalists. ‘Even groups like the IWW [International Workers of the World] in Oldham,’ Rob says. ‘They’re trying to revive syndicalism, but we couldn’t work with them due to the corruption of international socialism.’

They proceed to list the atrocities committed by socialists against anarchists: the suppression of the Krondstadt revolt and the execution of anarchists after the October revolution, Communist Party manipulation of the war in Spain. Here in this saloon bar, too: the weight of history. Showing in Kate’s face as she rages about these events which occurred before her birth.

I ask Kate how she feels about the current political situation. She says she feels very depressed. We all go our separate ways.

Another night, another pub, and another anarchist view of life from Michael, who says he gets less outraged and more cynical as he gets older. He is only 29, but has been through a number of things, including the Harrogate Anarchist Group, the Stoke Newington 8 defence committee and the Organisation of Revolutionary Anarchists. Michael has been up at the Old Bailey himself, charged with ‘conspiracy to effect a public mischief’; but these days he has withdrawn from what he calls ‘ official anarchist politics’. He now works for On Yer Bike, is an electrician for a housing co-op in north London, and an active trade unionist.

Michael started out in politics in 1968 with the Young Communist League. ‘They were still living in the cold war,’ he says. ‘Read your Lenin, be a good boy, live cleanly.’ But it was not just the YCL’s ascetism which turned Michael off. ‘I alsocame to believe that being a socialist entailed notions of equality which all hierarchical structures contradicted. That’s what led me to anarchism.’

Michael rolls his own cigarettes, has one ear-ring and a skinhead haircut. He says he got his haor cropped because he was working on a co-op that was full of ‘squatters-army types’, with hair down to their shoulders. ‘They think I’m strange. Last job I had was a straight job; those people thought I was strange, too. Blokes I used to work with, when they stuck up tit-and-bum pics I used to tear them down.’

He says that most ordinary life is about observing conventions, and he enjoys flouting them. ‘I ignore hierarchies. say you get some cretin of a supervisor who wants to be called Mr Blah – you call him “Squire”.’

The capitalist, in Marxist cartoons, is a fat man with a fat cigar; the workers are puppets in his pudgy fingers. The anarchist has more sense of the comic absurdity of those who crave wealth and power. The anarchist, too, has confidence in his/her personal ability to resist the diktats of the leaders. ‘Ain’t no fucker going to grind me down.’ The anarchist must be an egoist of sorts.

Two of the people Michael has tagged ‘suatters army types’ come into the pub, sit at our table. One has hair down to his waist. The other speaks very slowly, this slowness as a result of ECT treatment he received ina mental hospital. ‘I worked down t’ pit, in Wakefield, for six month,’ he says. ‘Fucking murder, man. I’m not doing that again.’

Six punks walk into the pub, and the landlord refuses to serve them. One of the women, bleached hair and black leathers, jumps up and down singing, ‘We’re too dirty. We’re too dirty.’ They leave and are followed out by another dozen who quickly quaff their drinks and walk out in solidarity. Michael takes the piss out of the man with long hair. ‘Didn’t refuse you a drink did they? See, it’s respectable now.’

For Michael, anarchy is ‘a way of living your life’. He lives in a squat, is not married, and says that he never will get married. The feminist message that ‘the personal is political’ has led Michael, like many anarchists, to experiment with life: anarchists are to be found these days around whole-food co-ops, housing co-ops and squatting groups, libertarian cafes, anti-nuke protest, animal liberation, cmmunity newspapers, women’s aid centres.

Hundreds of thousands of words produced for publication by this libertarian movement have been typeset by Ramsey, a worker at the Bread ‘n Roses co-op in Camden Town which, he says, is ‘the premier left typesetter’. But Ramsey, after a long involvement in anarchism, has now turned his back on it. ‘It’s the politics of individual paranoia.’

He now believes what most Marxists believe, that anarchism is an idealist philosophy. ‘It’s rooted in ideas of wouldn’t it be nice if . . . Instead of saying, this is the present, this is how we got here, this is how things change, the whole materialist approach. On the continent, anarchy is a more collectivist, class-based politics. Here anarchy was to do with the youth revolution, and the consumer society of the fifties and sixties.’

The most imaginative of the critics of consumerism, as Ramsay prints it, were the Situationists (who were the catalyst for the events of May ’68 in France). ‘They turned Marx on his head. Instead of saying that consciousness was determined at the point of production, the Situationists said it occurred at the point of consumption: this is the consumer society, the society of spectacles, spectacular commodity production. But there’s not many Situationists left. It fizzled out when the boom ended, and there was no longer any scope for talking about never-ending commodity production.’

Nicholas Walter, whose grandfather was a middle-class dropout who met Kropotkin at an ‘at home’, disagrees with the idea that the Situationists are burned out: ‘I think we’re much more Situationist now. This new book on poverty [Peter Townsend’s] shows how definitions of poverty have changed to include anyone who doesn’t have a television. Give them the dole and put lots of crap on the telly . . . And that lovely American cartoon showing a bombed-out landscape and a man walking across it with a TV set trying to plug it in. Of course, the Situationists themselves were part of the spectacle. Especially in France in ’68, there were TV cameras all over the place.’

Respected authority on anarchy (?), Nicholas Walter is now editor of the New Humanist and still a prolific writer for anarchist newspapers and magazines. He was introduced to the Freedom group by his grandfather. ‘I haven’t changed my mind in 20 years. I’m just more pessimistic now.’

What are the highlights of his anarchist career?

‘Spies for Peace in 1963. And the Brighton church demonstration in 1966, when I was one of the members of the group which carried out the interruption of the church service before the Labour Party annual conference. Also, the reproduction of James Kirkup’s poem, “The love that dares to speak its name”, when Mary Whitehouse prosecuted Gay News in 1976. I reckon I circulated more copies than anyone – even though I think it is a silly poem – on the libertarian ground that anything anyone wants to ban should be circulated.’

Anarchy in the UK was a Top Ten hit for the Sex Pistols in 1977. It introduced the word ‘anarchy’ to a new generation. It became fashionable again, for a time, to say you were an anarchist, to spit in the face of the normaloids. But most punk bands who attached themselves to anarchy were merely boarding the gravy train. That is why I went over to a cottage in Essexto talk to one punk band, Crass, who seemed to have thought more seriously about their anarchism.

A man in black with dyed blond hair – his name is Pete – pours tea for an old farm worker in the living room. Someone upstairs has Dr Roberts, by the Beatles, at high volume. We’re waiting for the rest of the band to come back from wherever it is they are; and when the farm worker has gone, Pete explains the various activities they have going here at Dial House. One of the women, he says, is away in New York, printing the latest issue of their magazine, International Anthem. Two other publications produced here are called The Eclectic and Existencil Press. A film maker lives and works in the cottage.

There is, too, what Pete calls a ‘graffiti operation’. He says they have taken over a section of the Underground. ‘We don’t just rip the posters down or spray them. We use stencils, neatly, to qualify them. Especially sexist posters, war posters and the sort of posters for sterile things like Milton Keynes.’ He spits those two words out.

‘A few of us going round and spraying with stencils reaches more people than the band ever could. It gives the people the feeling that something is going on; that there’s a possibility of something happening; that things aren’t all sewn up. You’re bombarded with media which you don’t ask for when you go from A to B and a lot of it is insulting and corrupt.’

‘But what have you got against Milton Keynes? What’s wrong with it?’ I asked.

‘I was actually working on the plans for the place. I started discovering what a complete shithole the place is. Cardboard houses, no facilities. It’s just a work camp, totally sterile, offers nothing.’

It was Steve who was playing the Beatles. He comes downstairs, runs his fingers through his Vaseline-spiked hair as he tells me he ran away from home seven years ago, and has lived in this cottage for two years. A woman who drifts in says that her name is Eve and that she sings in the band.

We talk about the various gigs that Crass have done – for Person’s Unknown, the Leveller, Peace News, Birmingham Women’s Aid – and the violence that has plagued their gigs of late. The band, it seems, has developed a following among British Movement skinheads. But Crass blame this on Rock Against Racism which, they allege, has polarised youth. ‘If you’re not in RAR then you’re a Nazi. Now we’re sandwiched between left-wing violence and right-wing violence.’

The rest of Crass show up: Andy, Phil and a man called Penny Rimbaud. Two children appear at the door and look around with interest. ‘Racism and mohair suits,’ says Steve, who has not said much up to now. ‘That’s the difference in punk music. Two years ago, you had Johnny Rotten standing on stage saying, “I am a lazy sod.” So where’s it all gone?’

What’s wrong with mohair suits, and anyway why is everyone in this room clothed in black? ‘Lots of reasons,’ Pete says. ‘Convenience. Anonymity. I’m doing the washing at the moment; it’s very convenient.’

We’re drinking tea in his room, which is filled with books, and I’m wondering which writers have influenced . . . ‘Zen and all its offsprings,’ interrupts Penny. ‘Existentialism.’

‘Zen and punk,’ smiles Andy.

‘The American beat movement,’ continues Penny. ‘Kerouac or Ginsberg.’ Pete says he hasn’t read Kerouac or Ginsberg. Andy goes off to make another pot of tea and when he comes back announces that, ‘Anarchy to me means living my own life, having respect for other people, respecting their right to do what they want to do.’

This is a long way from Black Flag, Freedom and anarcho-syndicalism. I doubt if Andy has read many books on anarchism, but he speaks of the kind of anarchy which has always been at the heart of rock’n’roll. It’s my party. Do anything you want to do. I can go anywhere, cha-chang, way I choose. I can live anyhow, cha-chang, win or lose. Anyway, anyhow, anywhere I choose . . . Take your desires for reality and make your reality your desires was, I think, one of the slogans of the Situationists.

One man who has remained true to himself through war resistance, two prison sentences, public-speaking campaigns on a long trail of causes, is Justin. Now, at 63, he is still active in Freedom. I met him over the road from the British Museum.

‘For me it all started with the Spanish revolution, grew with war resistance. And then you realise that war grows out of certain things in capitalist society. So you have to oppose the whole bloody lot. Nothing that’s happened since has made me change view.’ Justin is bearded, wears a black peaked cap, and a cord jacket. He drinks whisky.

‘A lot of intellectuals supported the movement in those days. People like Herbert Read, Alex Comfort, Ethel Mannin, all rallied round marvellously when Freedom was attacked in 1945 by the Special Branch. We were charged with disaffection of the forces; mustn’t tell the soldiers the truth about the war.’ He got nine months, and served six.

‘When I came out, the Special Branch tried to do me again for refusing to serve in the forces, tried to make me take a medical. I refused that and got a further six months, of which I did only six weeks because quite powerful papers like the New Statesman started to huff and puff.’

Justin remembers the days in the 1950s when he used to speak three times a week: once at Tower Hill, once at Hyde Park Corner and once at Manet Street in Soho. He remembers demonstrating at the Shaftesbury theatre when a dance troupe came over from Francoist Spain and he remembers occupying the Cuban embassy. ‘We just wanted to show everyone we were as opposed to the communist regime in Cuba as we were to the Americans in Vietnam. Plus the fact that Castro, as soon as he’d gone into power, had begun to lock up all dissident leftists. Same old story: use all the anarchists and libertarians to make the revolution; then get rid of them.’

He remembers a libertarian literary quarterly called Now, edited by George Woodcock and contributed to by George Orwell, who also wrote occasionally for Freedom when he came back from the Spanish civil war. ‘Orwell didn’t really agree with the anarchists, ‘says Justin. ‘But when we were attacked, by God, he came out and supported us; spoke at Conway Hall in 1944, a meeting on free speech. I chaired it. He was a straight man, straight as a bloody die. He respected the anarchists, because of what he’d seen in Spain.’

He remembers Spies For Peace too, and the campaign for the abolition of the death penalty (‘The anarchists kicked off that campaign and I’m particularly proud of that’).

Justin remembers enough things to fill a book, which is why he’s going to write one, when he retires in three years’ time. But most fondly of all, it seems, he remembers the Malatesta Club in Soho, which was run by the London Anarchist Group from 1954-8, seven nights a week. Habitues used to write songs and poetry and perform them at the club, which also had a resident jazz band. ‘I used to make up songs – sort of sing and shout, to a drum. Couldn’t play anything used to hammer away on the drum . . . it was really something, all run completely voluntarily.’

The anarchists’ coffee house (it never had a licence) was called the Malatesta because he was the only anarchist writer the group could agree on. ‘Some were Kropotkinists and some were Bakuninists, but we all agreed Malatesta was a good guy.’

‘There’s a man used to be in the anarchist movement in wartime.’ Justin is pointing at a man who’s just walked in, a woman on his arm. ‘Hello,’ says Justin to this old comrade, who smiles back briefly but doesn’t pause to chat.

I ask Justin if he’s ever doubted his views? ‘Towards the end of the war, when we saw the pictures of the Nazi camps, we wondered whether, after all, we had been right to oppose the war. But then the war ended with an atrocity from our side, Hiroshima. You can’t choose between any of those bastards.’

Sitting over a pint next to a man who has fought good causes for a good few years – against bombs and hanging, against spies and censorship, torture – you feel humble, and you wonder if you’ll have anything to say for yourself when you’re 60 and in a pub with someone 30-odd years younger? But there is one last question: does he still, deep deep down, believe that some of what he has fought for and dreamed about will ever come true?

‘You’ve got to think your ideals have got a chance before you’ll give your life to it.’

Two days later in the Drill Hall, just off Tottenham Court Road, the question under discussion is not so much about whether the ideals have a chance, but more what are the ideals? The meeting was organised by Solidarity, a libertarian group who draw on themes first developed by the ‘Socialisme ou Barbarie’ group in France. About 50 people are sitting on the floor, listening to a man called Akiva Orr, who says he is an ‘ex-Israeli’. He has no notes and uses his hands theatrically as he speaks. His cigarette, too, he holds as if he is on the stage.

The emphasis has shifted from the exterior to the interior, that’s it. Suddenly there’s an awareness that life, reality, meaning, dadadada, it’s all in there.’ His finger a gun to his head. ‘Used to be a time when meaning was all up there,’ he points to the ceiling. ‘Or out there,’ he gestures to the streets below the windows. ‘Now it’s shifting, it’s in here . . . There’s a jungle out there,’ he pauses for dramatic effect. ‘I mean in here,’ putting his hand to head again.

‘All I can say is that we’ve got to develop answers in this battle for the interpretation about what is real. We are the meaning-making animals.’

Someone sprawled on the floor drawls that he needs a coffee break. On the stairs leading down to the cafe a woman wearing a yellow T-shirt which says I AM A HUMOURLESS FEMINIST tells someone that her father-in-law is a judge.

Outside these windows, people are buying new stereos on the Tottenham Court Road; people are standing on football terraces; watching the TV; cleaning the car; knocking up shelves, watering the plants – whatever the hell it is people do in an attempt to relax on a Saturday afternoon. ‘The central human question,’ says a man in a black leather jacket, ‘is how to be happy without hurting people.’

The various critiques are over. Time for Akiva’s reply. He has great style, and he knows it. He has this audience in his hands. ‘We could expend a lot of time and energy discussing Marx. We want to discuss ourselves,’ he says, his hands pointing elaborately at his chest. ‘What do you want to smash when you say you want to smash capitalism? The police stations? Parliament?’

‘Yeah,’ someone shouts from the floor.

‘You must smash structures which are abstract, too,’ Akiva continues. ‘You won’t find them. They aren’t lying around. You have to construct them. Fuck the historical process. I want to construct a model which is enjoyable for me.’ He lowers his voice now to say, ‘But it’s not an easy task.’

The anarchist who wanted to smash up the police stations interrupts again. He is, someone tells me, a postman. There is a heated exchange between him and Akiva: the young activist versus the older intellectual. ‘I have a friend,’ says Akiva. ‘He spent the first half of his life constructing socialism in Czechoslovakia, the second half of his life dismantling that structure he spent the first half of his life building. The system has smuggled itself into your mind.Your own system will be a mutant of that system you set out to smash.’

Discussion over. Some will stay in the Drill Hall for the social tonight. There will be a real ale. I go out to watch Alien, and remember a drawing by an artist called Cliff Harper. It shows a spaceship landing in London. The Houses of Parliament have toppled from the impact of the laser beam attack. A woman holding a ray gun steps out of spaceship. ‘Take me to your anarchists,’ she says.

Ian Walker

Weller On Pop

From Jamming!, number 13, June 1982. The introduction is by Tony Fletcher (AF).

Weller On Pop

This piece was originally written as an introduction to an article in the NME that never saw print. Britain’s largest selling music weekly had asked Paul for an interview before Christmas, but instead Paul suggested he interviewed the writers and do the piece himself. Unfortunately, despite writing this introduction, Paul didn’t have time to finish the article. Therefore, what we’ve got here does lack a conclusion, but it still throws up many interesting ideas on pop, it’s press and the idea of ‘stardom’. This is not meant to be a defenitive statement, so don’t go accepting it just ‘coz it’s by Paul Weller – that’s the attitude the article is largely against. We would really appreciate all comments on this as trying to get further than just listening to music, and actually understanding the reasons for it’s existence, is a very difficult and untouched-upon subject.

NB – Please remember when reading that this was meant to be in the NME, co certain comments apply to them, not us – AF.

“London, Paris, New York, Munich, everybody talk about – pop music.” That’s Pop Music spelt S-H-I-T! South Africa, India, South America, Middle East, everybody talk about….

Pop Music – The modern working classes art. Van Gogh, Cazano, Picasso, Warhol, the whole of the Tate (hlaf of which is shit), Dickens, Wells, Shaw, Lawrence, Burroughs, Kerouac, William Blake, Shelley, Miller and thousande more I can’t pronounce, spell or have never heard of…. these artists aren’t for you! No, I don’t mean you reading this in the ‘dorm’ (tee-hee), or you the pathetic neurotic struggling student with middle class delusions who regularly write to the NME to “tell them what I think” and believe that there’s no such thing as the ‘Class system’.

No, I’m talking to you, Joe Bloggs; you the hoddy, you the unemployed 16-year old who buys his piece of middle class (with proletariat sympathies) rubbish every week. No, the afore mentioned artists are for the intellectual public, the educated mass of literate thinkers. Pop music, along with radio, TV, and cinema is your art! All created especially for you. Great eh?

Pop(ular) music is viewed by the select classes as –

a) Cheap and vulgar

b) Mindless entertainment for the mindless working classes, but

c) Very profitable.

Most pop music is cheap and vulgar; a lot of it is fucking mindless; and certainly it is very profitable. Most of the time it stays this way because unlike ‘Higher Art’, the class that pop music rightfully belongs to and is directed at has no control over it. We have no control over it’s media – TV, radio and the music papers – and obviously it’s profits. I have actually earned a lot of money out of pop music but it’s still nowhere near what record companies, publishers and promoters can earn. Even though since punk we have seen the rise of these people in the independent field (and good luck to you), it’s still not enough. There should be a greater liason and structure nationwide for groups to work together. But then again, we are in a very competitive line of art – most groups hate each others guts. The ‘Rough Trade’ groups hate people like The Jam because they think we are crass because we are signed to a big label (which is a fucking joke!). I hate them because they’re so drab and colourless, but I admire their independence. I especially respect groups like Crass who actually live the life and ideals they sing/shout about. I also love groups like Madness, big label or not (and with little control over their output), because they bring real joy into my heart. I dislike the so-called ‘Underground’ groups who are happy to belong to an elite section until they realised they weren’t getting anywhere, and so opted for crass, vulgar and mindless pop-kids market (hi Adam, Teardrops, Human League, O.M.D., and a whole lot more):- the music is nice and pleasant, but the about turn in attitudes makes me cringe.

When the obligatory question “Do you think success has changed your ideals or watered them down?” arises, I can quite honestly say no it hasn’t. In fact I’ve grown more idealistic in the last three years than when we started. When I was 18, all I could think about was becoming famous and a star. Now the though of stardom makes me feel sick. Pop stars are generally one of the most self-centred, unhealthy, big-headed bunch of wankers around, so why would I wish to be associated with people like that? Look at all the best pop groups – Madness, The Beat, TV21, Department S. etc etc – and you’ll find that most of these people love the idea behind pop music, but loathe pop stardom. And quite right too. You can create good pop music, cultural and intelligent; you can get people’s minds, feet and imagination going, without resorting to base gimmickry and mindless lyrics.

The pop papers supposedly exist to reflect what is going on in music, to introduce new groups/styles and to expose the musical charlatons. And hear hear I say. But whatever they say they they are practically always innacurate, always just that bit too late (look how long to pick up on punk and the Pistols), or otherwise just plain self-indulgent. All the papers are run by old men, certainly compared to their readership. Their criteria is limited and also unobjective.

Some of the writers are very nice people – quite real and honest – but I would say the majority are wankers. A lot worse than the pop stars they write about, and that’s saying something! (By the way, it will be interesting to see who slates me/us after this as well!). Some I have met really believe they are something special, that you dear reader rely on them totally to give you the info and views that you desperately need – this is true! They honestly believe they are up there with the Big Cogs of the Wheels of Music. Fucking hilarious, innit?

Paul Weller

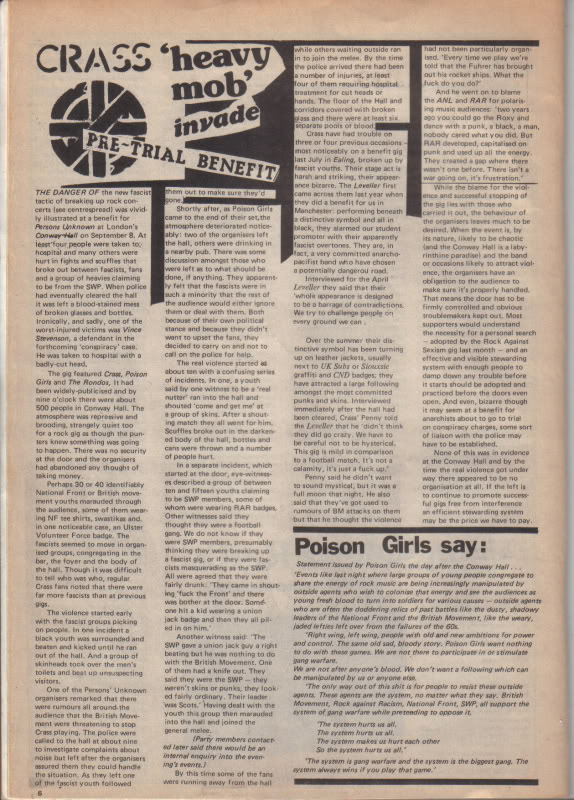

Crass – Conway Hall

On 7 September, 1979 Crass did a gig at the Conway Hall as a benefit for the Persons Unknown trial. The gig was attacked by a heavy BM mob and the call went out from some people present to the anti-fascist squads who turned up and dealt with them.

Crass were not happy and blamed the violence on the politicisation of punk by Rock Against Racism. Really!

Even weirder, given Crass’ much touted pacifism (seen by many as an avoidance of class politics) those involved in the trial were up for causing explosions.

The Leveller, October 1979 reports on the gig.

A History Of Zines

A history of fanzines, and a pretty good one too, from Marxism Today, June 1984.

FANZINES

Paul Mathur

Remember that old chestnut The Day Punk Rock Arrived? In a hail of gob and a parade of One Chord Wonders, the message was sent that ANYONE can be a star, and without selling one’s soul to the big companies. The Independent Ethic, hitherto only widespread among the 60s US garage bands, was reborn and flourished, most successfully in the form of Zoo Records from Liverpool, Factory from Manchester and Rough Trade in London. Rough Trade even took things a step further, and set up a nationwide distribution network, centred around teir shop in W11. Seven years later, and the company and shop remain. Go in there now, and you’ll find amongst the inevitably massive collection of independent records, an equally inevitable piece of post-punk product, The Fanzine.

The titles will scream out at you from the roughly stapled, cheaply printed (or photocopied) magazines — Kill Your Pet Puppy, Search And Destroy, Love And A Molotov Cocktail. Dig deep and you might even find a copy of No More Masterpieces, my own two year contribution to the fanzine scene, from 1979/80.

The ‘zines vary in content (ranging from anarcho-political tirades, to pages and pages of live reviews); in articulation (from powerfully convincing arguments about the musical scheme of things to monosyllabic grunts about what Crass did for an encore); and in form (handwritten scrawl to neatly typed pseudo-New Musical Express regularity. It is not easy to classify fanzines in terms of appearance, and it is even harder to do so in terms of history, for although fanzines are central to an understanding and an historical account of pop music since 1976, it’s very difficult to attribute any date to the birth of the music media’s bastard child.

There probably isn’t such a thing as the first fanzine (literally ‘fan magazine’) in the strictest sense of the word, although the likes of Oz and more specifically Rolling Stone, were instrumental in both presenting a radical message about the role of pop in youth culture and also publicising and organising the Underground Press Syndicate, a similar system to which is vital to the publicity and distribution structure of post-76 fanzines in Britain.

Rolling Stone, taking the lead from yet earlier Underground pop papers such as Copenhagen’s Superlove, was launched towards the end of 1967 by Jan Wenner, a 22 year old who at the time took much from Superlove’s ideas and forms. It is easy to see now where his heart really lay. Rolling Stone is perhaps the least contentious, most boring music paper in the Western world, as much a part of the capitalist music machine as CBS or EMI. The turnabout from radical champion of a burgeoning youth culture, to reactionary upholder of desperately conservativ values, is one that almost every fanzine is in danger of going through, but which the pre-punk ‘zines were most obviously susceptible to.

From reading a fairly large sample of these 60s and early 70s fanzines, particularly those primarily concerned with music, the most striking aspect is their deeply ingrained, and often barely concealed RESPECT for the music business. Hot Wacks, Fat Angel, Who Put The Bomp, Zig Zag, they all appear to want to play at being a sort of Melody Maker Meets Zen And The Art Of The Guitar Solo. Fat Angel for example, opens up with a bit of vaguely mystical hokum, then launches into a series of LP reviews, going so far as to give the serial number of each record. There’s no swearing, no feeling of any attempt to really communicate to the reader, no notion of the role of the fanzine as being anything more than an inferior version of its mainstream peers.

These ‘zines do succeed when they openly acknowledge their attitudes to the role of the alternative press, and where rather than churning out sub-standard music press copy, they attempt to cater for people who want something different from the music press. The form remains boring but the content changes, and the magazines start to run features on, for example, collectors’ records.

Who Put The Bomp and early Zig Zag both made their names and reputations as collectors’ magazines rather than as fanzines, and it is in magazines such as those that the power of the 60s/early 70s alternative press lies. In 1976, along came punk with its attendant ethics, and suddenly the fanzine became a whole new form. The first (and most notorious) of the ‘zines to reject most of the old traditions, preferring a passionate, emotive, wholly personal slapdash POW! to a merely shoddy attempt to be like the big boys, was Sniffin’ Glue, started by Mark P, and it remains the most perceptive contemporary account of the early days of punk yet seen. In a typical issue Lou Reed is written off in four lines, interviews are printed verbatim, captions handwritten, the whole lot photocopied and stapled together, then ‘sold’ outside gigs in a tone you wouldn’t want to refuse if you valued your teeth.

1977 and the walls were falling down everywhere. Thousands took Mark P’s advice and started their own fanzines, at last having to face up to the logistics of the affair. I was lucky, my Dad got mine printed for me at work, but for many others it was a case of trying to get them done on the sly in the school printroom, or failing that, looking for the cheapest printer in the yellow pages. Community printers are a great help, as they tend to be fairly cheap, and since the people doing the printing are fairly supportive of your cause, it’s easy to discuss with them exactly what you want done. Whichever way you do it, on each issue with a cover price of 25p, at least l0p of that will go on printing. Running a fanzine is a difficult business, and a combination of high costs, distribution problems and a fiercely protective set of writers, brings up the real failings of the ‘zine.

Being so closely connected to the scene they are writing about, groups are hugged to the breast of the editors, lauded as the Best Thing Since Breakfast, and then expected to fit into the role that the fanzine sees for them. Any progression is declaimed as a sell-out and the group are cast away or smothered with contempt. The groups move but the fanzines stand still. It’s all too easy for the most potent and revolutionary of forms to become as reactionary as the 60s NME that shrieked with horror when Cliff wiggled his torso. Kill Your Pet Puppy says don’t twitch your hips Clashboys! Such an attitude has meant that the majority of fanzines have given rise to a self-consuming culture. ‘Anarchist’ groups such as Crass, products of fanzines, find themselves pandering to them and slowly being hemmed in, not wanting to disappoint the concrete foot (and brain) fans, and so not being able to break away from an increasingly narrow direction. Their inability and unwillingness to break away is interpreted as a condoning of the fanzine system.

Fanzines must not slip into this reactionary stance if they are to use their potentially explosive existence. The youth culture of the past 25 years has liked to think of itself as self-contained, whereas in reality the power lies with the multinational record companies and mainstream music press. Selling this culture back to the masses is the major consideration, and the mainstream press are able to act as a filter between company and consumer, distancing and containing any unwanted ideologies, couching them in the cotton wool of musicbiz rhetoric.

The fanzines have the power to change this. They are literally by, and for, the fans, and are providing the impetus for representation of the culture from within the culture itself. This is dangerous to the dominant ideology, challenging it directly and powerfully. Fanzines must be aware of this if they are to use their power to change the structure of the music business and in turn that of society itself.